The winner of the Owen-Rowley Sculpture Prize in 1991 and the Sculpture Prize at the Victoria and Albert Museum “Inspired by the Human Form – The Founders’ Award” in 2007, Sophie Dickens sculptures have earned important critical acclaim at exhibitions here and abroad and she has ardent fans of her work in the US as well as in England and France.

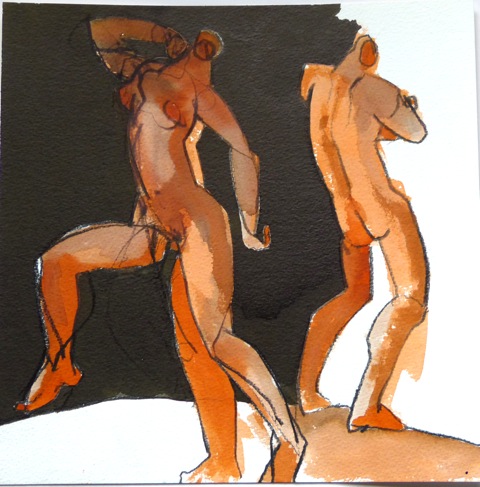

Sculpture and Decorative Arts Department, and former curator of 15th Century Paintings at London’s National gallery, said in part, “Sophie Dickens’s Adam and Eve is a masterly and extremely moving exercise in balance. …..She has created a compelling image of vulnerability and despair ….Dickens employs both jutting relief and airy voids to establish the anatomy of her figures and, still more importantly, their sacred and very human predicament.”

Sophie Dickens is the great great granddaughter of Charles Dickens, currently in his bicentenary year. She attended the Courtauld Institute where she studied the High Renaissance by day and painted the human figure by night.

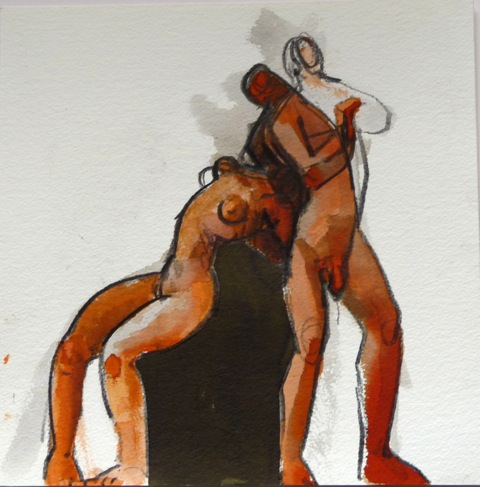

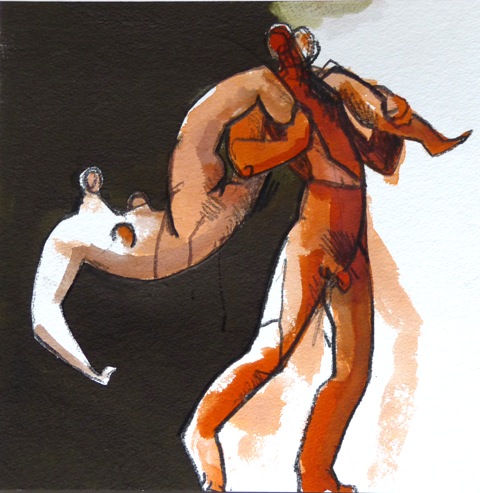

“I never stopped going to life classes,” she says, “I was always trying to get to grips with anatomy.” Learning practical skills came later training under Clive Duncan at the John Cass School of Sculpture in White Chapel. Then, at The Slade’s course in anatomy, Sophie acquired a proper understanding of muscle, bone and sinew.

She says, “The earliest sculptures ever made, in nascent cultures throughout history, were figurative and were used to explain the inexplicable - fertility, the weather, divinity, omnipotence, powerful magic. The most important part of my education as an artist was the study of the history of art - the history of physical human expression and the manipulation of others, a means of making a non-verbal statement about who we are and what we believe, whether artist, patron or commissioning body.

“For me, the wonderful thing about relating sculpture to the human figure is that nobody is excluded from it. Through the application of pieces of wood onto a steel armature I can convey emotions and preoccupations that are meaningful to me - vulnerability, spiritual energy and the Don Quixote-ness of man’s struggle with his own humanity.

“My technique evolved from the traditional modeller’s practice of packing out armatures with pieces of wood before applying clay to the form. I started using curved pieces of wood, creating an interplay of concave and convex surfaces that relate to anatomy and movement. The faceted surfaces translate very well into bronze, accentuating the jutting reliefs and airy voids that inform the momentum and physicality of the sculptures.

Gradually her passion for clay graduated to a fascination for working in the malleable yet crisp medium of wood. "I wanted the anatomy to show, but not as if the figure had been flayed," she comments. It takes confidence to combine immediacy alongside references to the art historical canon."